Between Headlines and Numbers: Tracking What We Can’t Yet See in AI Buildouts

A look at what’s still opaque in AI infrastructure disclosures.

While most of my articles take a deep dive into a single story, the “Between Headlines and Numbers” series is a little different. It brings together several shorter notes - some based on in-the-news developments, others involve a brief follow-up on stories that I’ve written in the past, and a few sparked simply by items that caught my attention.

In this roundup, I’m highlighting three threads I’ve been following closely.

First, a discussion of a construction-in-progress WSJ piece that quoted my take on the limitations of the AI-related disclosure.

Second, an update on the SEC’s observations on AI disclosure and accounting during the December 2025 AICPA conference, in particular those pertaining to useful lives of fixed assets and single-use entities utilized to finance the construction of data centers.

Finally – and unrelated to AI – the PCAOB sanctions against an accounting firm I previously flagged in Deep Quarry.

I was recently cited by Mark Maurer in a WSJ piece which explains limitations of AI-related disclosure in financial statements – specifically, the lack of disaggregation and diversity in practice of the construction-in-progress disclosure:

“The disclosure is not evolving quickly enough to keep up with real-life demand for information about AI investment,” said Olga Usvyatsky, an accounting consultant.”

Construction in progress (CIP) is a temporary accounting category within property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) used to accumulate costs for assets that are not yet ready for their intended use. During construction, companies record spending on materials, labor, equipment, and related capitalized costs in CIP instead of depreciating them. Once the asset is completed and placed in service, the accumulated balance is transferred out of CIP into the appropriate PP&E account and depreciation begins.

CIP numbers are substantial and keep growing, reaching almost $215 billion for companies with AI infrastructure, according to WSJ:

“Construction in progress collectively totaled about $214.5 billion this year for public companies with at least a $2 billion market capitalization that referenced AI infrastructure in their filings, according to investment research software provider Hudson Labs.”

Yet, here is the problem. CIP often aggregates spending on land, data center buildings, power and cooling infrastructure, and servers into a single balance sheet line with limited detail, despite widely different depreciable lives of 20 to 40 years for buildings and up to 6 years for servers. Because companies rarely break out the portion of CIP that relates to a specific AI project or disclose how project costs progress over time, it is difficult for investors to track the progress of these projects toward completion or to understand how much depreciation is expected in the next year.

I wrote about construction-in-progress disclosure limitations before – in the context of GPU depreciation and, together with my friend and frequent collaborator Francine McKenna of The Dig, in our joint analysis of Tesla’s CAPEX spending.

But before we dig deeper into analysis, let me also use this opportunity to say a big thank you to Francine - even when her name is not on the piece, she is often my go-to person when I need an extra pair of eyes for complex technical matters.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no explicit GAAP requirement to disclose CIP balances or to show separate lines for buildings and servers within the CIP categories. While the CIP balances are becoming more significant, it is difficult to understand AI-related CAPEX given the current disclosure limitations.

“In plain English, the numbers in the table tell us that, for companies in my sample, the staggering 18% to 38% of total PPE as of the most recent fiscal year-end was not in service and therefore not yet being depreciated. Once these assets are placed in service, the depreciation expense is likely to increase dramatically.

And – the last for this piece one-trillion-dollar question: Can we put a number on this additional depreciation? The answer is: not directly from the financial statements due to disclosure limitations.”

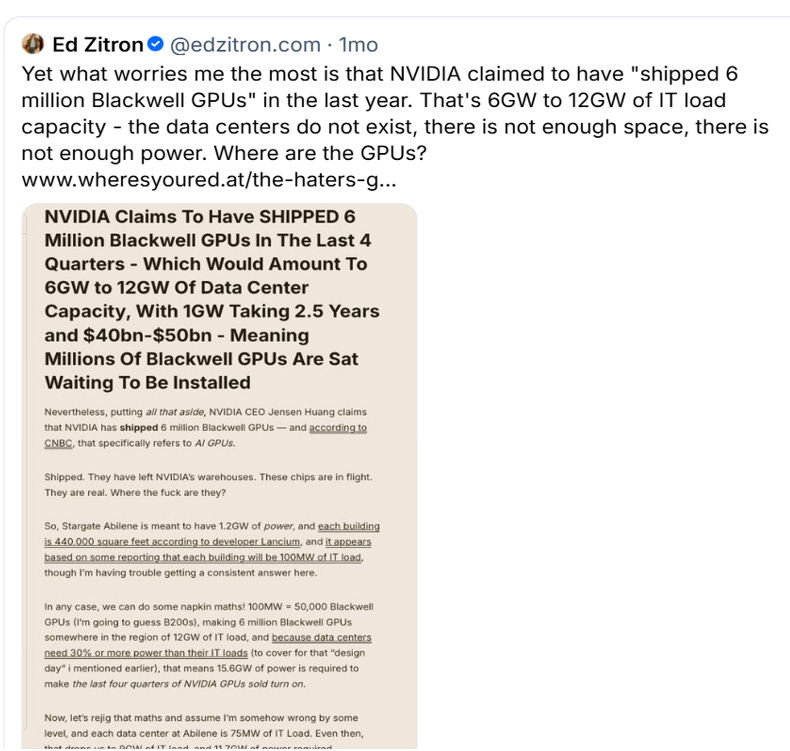

The CIP issue came up in one of BlueSky’s conversations that I followed. Ed Zitron noted on BlueSky that, according to his analysis, Nvidia shipped millions of GPUs, but only a fraction of them were installed:

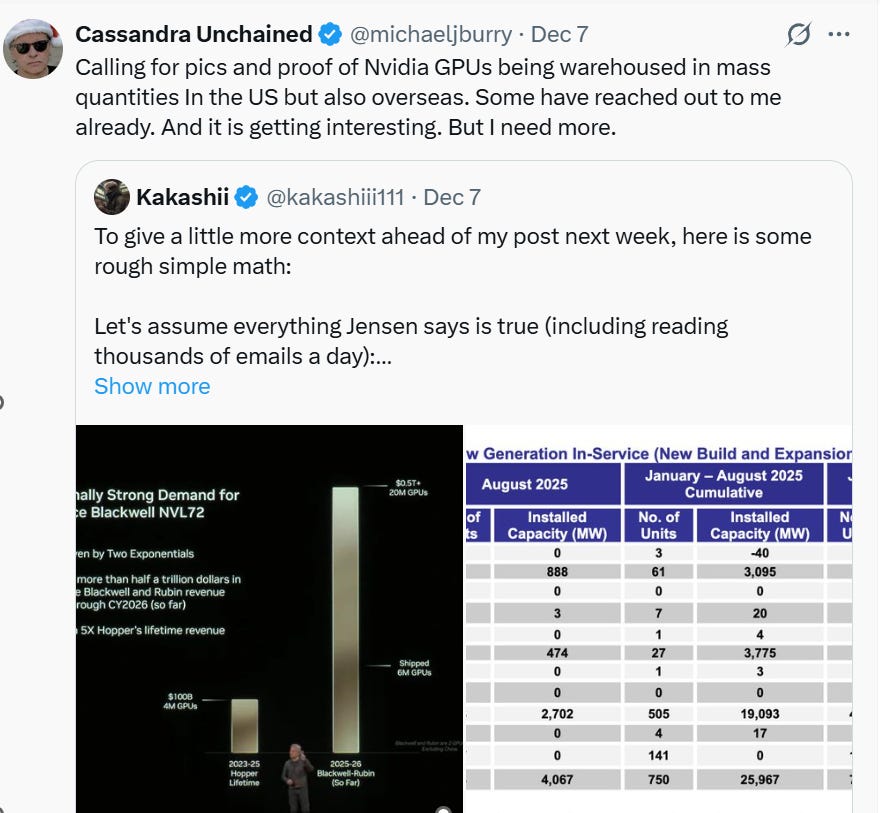

Mike Burry, a prominent investor and the “Big Short” lead character, echoed a similar sentiment in his X post:

So, where did all those GPUs go, and how can we trace them in the financial statements at a company level? In my view, purchased but uninstalled GPUs currently sitting in the warehouses are likely reported as construction-in-progress in the financial statements.

However, we are back to square one: because of the disclosure limitations, investors cannot currently allocate the CIP numbers between relatively short-lived GPUs and longer-lived infrastructure investments.

Regulatory Scrutiny

Let’s shift gears and look at where the SEC stands on efforts to enhance disclosure and enforce AI-related accounting. The hot topic of AI accounting came up on several occasions during the 2025 AICPA & CIMA Conference on Current SEC and PCAOB Developments.

During the conference, the SEC reiterated that companies must continually reassess the useful lives of long-lived assets—significant AI-related capital spending does not change the requirement to select and update depreciation periods based on actual usage, and impairment charges are not a substitute for adjusting useful lives when conditions evolve.

From Deloitte’s summary of the conference:

“Fixed assets — An issuer may need to determine the useful life of the data center and any related long-lived assets (because, for example, the issuer consolidates the entity that owns the data center and related assets). Ms. Karafiat reminded preparers that ASC 360 requires entities to continually evaluate the appropriateness of useful lives assigned to long-lived assets. Further, Ms. Karafiat stated that the SEC staff does not view the recognition of an impairment of a long-lived asset as an acceptable substitute for determining the appropriate useful life of the asset. However, when an entity is performing a recoverability test of its long-lived assets, ASC 360 requires an estimate of cash flows based on the entity’s own assumptions about its use of an asset or asset group. This estimate should incorporate all available information.”

In other words, when companies build or control data centers, they must keep asking themselves how long those assets will realistically stay useful. The SEC’s view is that you can’t treat an impairment charge as a patch over a leaky roof - companies need to set the useful life correctly up front and update the estimate as conditions change. And when testing whether those assets will earn back their value, the rules say companies must rely on their own cash flow assumptions and all the information at hand.

Another AI-related issue that came up during the conference is accounting for single-asset entities used to finance capital-intensive projects, such as data centers, often employing a Variable Interest Entity (VIE) structure. A Variable Interest Entity (VIE) is a legal entity whose financial results must be consolidated by another company if that company has both the power to direct the activities that most affect the entity’s economic performance and an obligation to absorb its losses or a right to receive its benefits. In other words, even without majority ownership, a company may need to put a VIE on its balance sheet if it effectively controls and is exposed to the economics of that entity.

The SEC observed that companies need to carefully evaluate whether these VIE entities should be consolidated, which could dramatically increase the level of debt on the consolidating entity balance sheets.

To sum it up, regulators are paying attention to AI-related CAPEX accounting, and changes in accounting may materially increase debt or depreciation expenses.

SEC Comment Letters

SEC Corp Fin has the tools to press for more decision-useful AI disclosure through the comment-letter process, and Corp Fin’s Chief Accountant Kurt Hohl noted during the AICPA conference that AI is an emerging financial-reporting issue. However, it’s still an open question whether the CAPEX side of the AI buildout will draw a more substantial Corp Fin attention.

We haven’t seen AI-capex comments surface in 10-K reviews yet, but the SEC’s IPO comment letters can be an early indicator of where potential scrutiny might be headed. The recent exchange with WhiteFiber, Inc. (Ticker: WYFI), an HPC data-center operator, hints at the types of questions that could migrate into SEC comments on periodic filings - particularly around power agreements and progress of data center construction.

Power Supply Agreements

In its initial SEC review of WhiteFiber’s IPO filings, the staff specifically asked the company to explain how its data centers obtain electricity and whether it has any power purchase agreements:

“We note your response to prior comment 12 that there are no material power purchase agreements in place at the Company’s HPC data centers. Please explain to us the method by which you receive energy at your HPC data centers and the costs for receiving such energy. To the extent you have power purchase agreements in place, please disclose the material terms of these agreements and file these agreements as exhibits to your registration statement pursuant to Item 601(b)(10) of Regulation S-K. Alternatively, please provide an analysis as to why you do not believe these agreements are material.”

WhiteFiber responded that its Québec facilities rely on standard Hydro Québec commercial tariffs passed through via landlords or direct billing, with no long-term PPAs filed as exhibits – put it differently, WhiteFiber is relying on the grid to power its datacenters:

“As described below, the Company does not have material power purchase agreements in place at its data centers. For the following reasons, the Company does not believe that further disclosure in the registration statement is required.

At MTL-1, the Company obtains its hydro power through the landlord, who recharges them directly based on actual consumption. The rate is a standard rate offered with no fixed term. The landlord owns the building complex and does not have a separate power entrance exclusively for Enovum. Their power is obtained from Hydro Quebec.

At MTL-2, the Company will be charged directly by the power provider, Hydro Quebec, at the commercial consumer rates. Again there is no fixed term.

In the province of Quebec, all of the hydroelectric power is provided by a crown corporation, Hydro Quebec. It has predetermined rates depending on the customers’ industry and based on the power demand. For the reason, there are no power purchase agreements forour HPC data centers in Quebec, which includes MTL-1, MTL-2 and MTL-3.”

This line of questioning matters because power is not a minor cost for AI infrastructure firms - it is core to both the timing and economics of deployment. AI and high-performance computing facilities have exceptionally high, continuous energy demands, and access to a reliable, contracted power supply can materially affect project viability, cost structure, and schedule.

Grid constraints are increasingly becoming a bottleneck: Bloomberg reported that power limitations have forced Nvidia to keep two Silicon Valley data centers idle, and Alphabet’s $4.75 billion agreement to acquire Intersect, a developer of advanced U.S. energy projects, underscores that securing generation and interconnection capacity is now strategic, not ancillary. In that context, it is worth paying attention to whether an operator relies on spot tariffs, long-term power purchase agreements, or project-specific energy partnerships to meet its power supply needs.

Project Status

In Question 1 of the May 21, 2025 comment letter, the SEC asked WhiteFiber to spell out what it actually means when it says MTL-2 will be “completed and operational,” MTL-3 has a “targeted go-live date,” and NC-1 will have “initial capacity energized”, and to describe the remaining phases of development needed to reach the profit margins it is marketing. In Question 3, the staff went further and required a reconciliation of the megawatts: how MTL-1, MTL-2, MTL-3, and NC-1 add up to 16 MW by the end of 2025 and then to roughly 76–80 MW by the end of 2026, including the contribution from a proposed upstate New York project. (WhiteFiber’s response is available here.)

The “complete and operational” language is not just a figure of speech in the IPO prospectus: that phrasing determines when CIP becomes depreciable PP&E and when revenue and margins actually materialize.

PCAOB Sanctions Against Fruci & Associates II, PLLC

On a completely different note, on December 18, 2025, the PCAOB sanctioned Fruci & Associates II, PLC and Jennifer A. Crofoot, a former audit partner of the firm, for violations of auditing standards in connection with the audits of four public companies: Clean Vision Corp., Hammer Fiber Optics Holdings Corp., LeeWay Services, Inc., and Zeuus, Inc. The PCAOB found that Crofoot, as engagement partner, issued unqualified audit opinions without performing adequate audit procedures on material accounts, did not obtain the required engagement quality reviewer concurrence, and violated audit documentation requirements.

Crofoot was censured and barred from associating with a PCAOB-registered audit firm for three years and must complete 40 hours of PCAOB-focused continuing education before petitioning for reinstatement. Fruci & Associates was censured, fined $50,000, and must implement remedial quality control actions following PCAOB findings that the firm failed to maintain adequate audit documentation systems and oversight to detect and prevent Crofoot’s conduct.

I previously flagged the deficient audits in Deep Quarry, noting that Clean Vision, Zeuus, and Hammer Fiber Optics had not disclosed whether Fruci’s audit deficiencies were self-identified or surfaced through PCAOB scrutiny - a disclosure gap that hinted at deeper quality-control problems now confirmed by the sanctions:

“Clean Vision Corp, Zeuus, and Fiber Optics Holdings Corp did not disclose how Fruci identified the audit deficiencies – namely, whether the discovery was prompted by the audit firms’ internal review or a PCAOB inspection.”

Audit deficiencies that raise to the level of incomplete audits force clients to go through a re-auditing process, possibly undermining investors’ confidence in the reliability of the financial statements.

For questions and data inquiries please contact olga@deepquarry.com.

Investment, Tax and Legal Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment, tax or legal advice. The content contained herein is not to be relied upon as the basis for any investment or other decision. Nothing herein should be construed as a solicitation, recommendation, endorsement, or offer to buy or sell any particular security, product, or service. The author has not taken into account the specific investment objectives, financial situation, or particular needs of any specific person who may read this material. Investing involves inherent risks, and there can be no guarantee that any investment or company mentioned will be suitable or profitable for any investor’s investment portfolio. Readers are strongly advised to conduct their own thorough research and consult with a qualified and licensed financial professional and legal counsel before making any investment decisions. Past performance is not indicative of future results.